Here’s what that taught me

I’m the target of good-natured ribbing in my upper-middle-class New Jersey suburb for my spending habits. My wife’s friends told her they’ll pass on going on vacation with us because I’m too cheap and would probably take a bus from the airport, pack sandwiches, and stay at budget hotels.

Guilty as charged. That’s in part because both my mom and dad spent money like there was no tomorrow when they were kids. They had to–there was no time to waste.

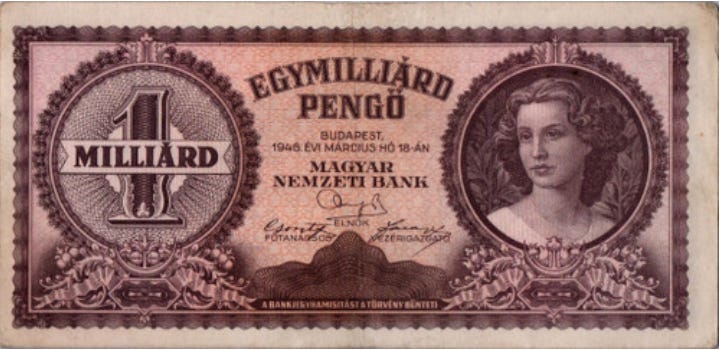

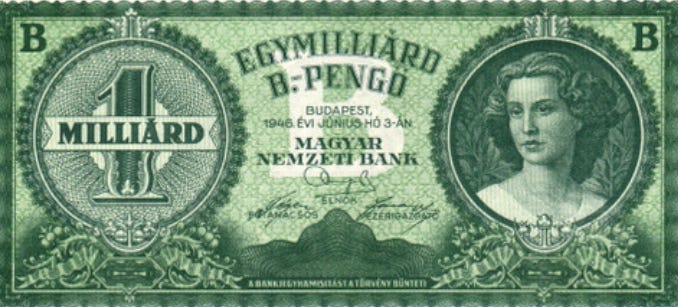

Without running water or medicine, hardly any food or clothing, and her father murdered by the Nazis, my mom was the poorer of my parents, but she managed to save a little bit of money in 1946, the year she turned five, to buy herself some candy. The banknote she had probably made her a local currency billionaire, yet it was literally worth less than the paper it was printed on by the time she was ready to spend it. My grandmother didn’t have the heart to tell her. With both of his parents still alive and the wisdom of being a decade older, my dad had a few more zeros on his net worth–not that it mattered much.

That was the insane reality in postwar Hungary. From time-to-time I’ve quizzed my colleagues in finance or journalism about which country had the highest inflation in history. They almost always guess Weimar Germany, Brazil, Zimbabwe, or, occasionally, early 1990s Yugoslavia. Nope.

In that fateful year Hungary’s inflation rate hit 41,900,000,000,000,000%. Not a year—a month. At the peak it took about 15 hours for prices to double. I once asked my grandmother how often she was paid and what she did with the money. Couldn’t she just throw it out the window on her lunch break for someone to buy groceries with it before they changed prices on her way home? She just smiled and shrugged. Nobody really wanted to hang on to cash so the main value of her job was that they fed her. She said that if you really needed medicine then the only way to get it was if you had a little bit of gold, which she didn’t.

Here’s the sort of thing my mom might have had in her pocket–a billion pengő–though maybe it was just 10 million, or a million or a thousand, depending on exactly what month she set it aside. (Milliárd=billion in Hungarian).

To keep things somewhat manageable, and to save scarce paper, old bills were printed over and reissued in denominations with nine zeros removed–the millpengő. That only lasted for several weeks, so then came the billpengő. (Billió=trillion).

Three months after the above bill was produced, the government printed, but never issued, a sextillion pengő note (one followed by 21 zeros). Then they gave up and scrapped the currency entirely, introducing the forint and making every pengő legally worthless. (I have almost the full collection of banknotes at home, but unfortunately not the rare specimen below, which is worth about $7,000 today to a collector).

Lots of people have parents who grew up poor. It usually makes you a bit frugal–no bad thing in moderation, though sometimes people don’t want to take trips with you 😢. But having almost no money and seeing money cease to have meaning are two entirely different things. To me, at least, those stories make any level of wealth or savings seem ephemeral.

It’s hard to imagine that in a country as blessed as the United States, the issuer of the world’s reserve currency. We have an “exorbitant privilege” compared with people whose wealth, salary, and future pensions are denominated in rubles, bolívars, dirhams, ringgits, pesos, reais, or, sadly, forints. Everything from the cars in our driveways to the appliances in our homes and smartphones in our pockets are more-likely-than-not procured from industrious foreigners who gladly accept electronic bits and bytes representing dollars. Since we don’t have as many useful things to sell them, the surplus is recycled into our financial system. Trillions of dollars are parked in Treasury bills, notes, and bonds earning hundreds of billions in interest annually. With a budget deficit of $1.8 trillion last fiscal year–the second biggest ever–the interest is effectively deferred, with no anxiety about it being paid.

You can read plenty of clickbait nonsense on the internet from doom-mongers comparing America’s fiscal future to Weimar Germany or Zimbabwe (they would cite Hungary if they or their readers were more aware of history). Things would have to go very, very wrong for that to happen.

But we certainly could get a whiff of it. I’m surprised how little my educated friends and neighbors question the solidity of our currency. It’s just a construct, backed by nothing but faith in America’s centrality to the world economy, the wisdom of its leaders, and its military might.

My wife and I had dinner this past weekend with two couples who also just shipped their youngest child off to college this year. The conversation soon turned from roommates and majors to the next exciting stage in our lives after becoming empty-nesters: retirement. One dad is old enough to have started collecting Social Security. While he could have gotten more if he had waited longer, I pointed out that it probably made sense to start taking it now because the retirement trust fund could be depleted in nine years. That was news to him and the others, but it was sort of like someone telling them the sun will one day consume the earth in a supernova–the sort of weird, theoretical thing they expect to hear from the nerdy finance guy they know, not an actual concern.

One reason most people aware of that projection by the government’s actuaries also don’t take it seriously is that they assume the federal government will step in and cover any projected shortfall. Paid for with what, though? Even on the outright panglossian projections of the Congressional Budget Office, which foresees no recessions, wars, or crises ever, Social Security, Medicare, and other mandatory outlays will be more than $6 trillion in 2033.

Meanwhile, debt held by the public will have doubled by that year to almost $50 trillion on those benign assumptions, and just the annual interest bill is projected at $1.6 trillion. Yet the model concludes that sane people will lend Uncle Sam the money to cover that interest due plus a deficit approaching $3 trillion for just 3.5% a year. That’s less than the yield on any Treasury bill, note, or bond being sold today.

So will politicians double payroll taxes on people still working or tell retirees that they’re out of luck and that they need to accept a third less each month? Probably neither, but you might not love the alternative. It’s something not totally unlike what Hungary was forced to do in 1945 and 1946. While the economy won’t be in ruins (I hope), the U.S. has an active central bank, borrows in its own currency, and does have a printing press. They don’t even need to worry about issuing banknotes any more because money is mostly electronic. Buying bonds and keeping interest rates artificially below inflation, dubbed “financial repression,” is one indirect way of doing this.

Is that outlandish? Between the prospect of doubling or tripling taxes, what would you expect Washington to do? Taking a step so likely to spur inflation is in-and-of-itself a form of taxation and is dubbed “the cruelest tax” because it raises money from people who live on a fixed income.

Before you pore over the actuaries’ report about Social Security, that might not be the thing that breaks. A war, a financial crash, or another pandemic could all push us close to the precipice. Or it could be that the scales fall from our creditors’ eyes one day and interest rates start to rise on their own, forcing the Federal Reserve’s hand. There is some speculation that the moment is nigh, though that has been predicted prematurely many, many times.

None of this remotely means the dollar will go the way of the pengő, but seeing our savings lose a third or a half of their real purchasing power would be pretty lousy. I started off this note telling you how annoyingly frugal I am. If my fears about the fragility of our currency are justified then I’m doing the exact wrong thing. I should be living it up and accumulating possessions instead of saving as much as I can.

If you see a new car in my driveway or hear that I’ve been flying business class and staying at The Four Seasons, that might be why. After all, I’m the child of billionaires.