Shame if something happened to it.

There’s a type of person I know who’s very educated yet shockingly naive about some things. We all have our biases and blind spots so I’m sure the same applies to me, but I don’t think it does about yesterday’s electoral earthquake in New York City. I’ll state from the outset that this isn’t a political newsletter: I don’t support a candidate, am not registered to any party, and I’ve never given money to one.

I also no longer live in the city—I just go there a lot, including for work. I guess that makes me one of the “bridge and tunnel crowd,” but I’ll always feel like a New Yorker.

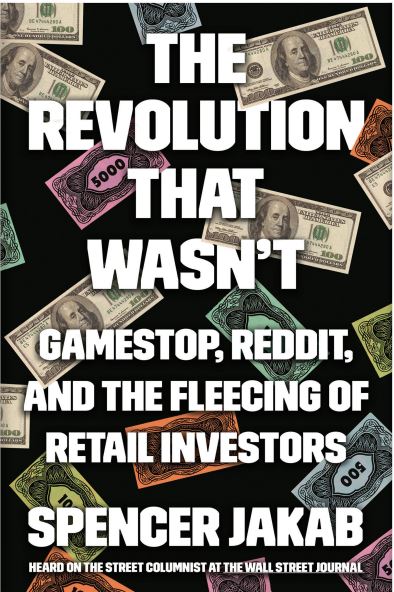

The man the aforementioned educated folks are relaxed or even excited about having as the next mayor of the country’s largest city and business and cultural capital is Zohran Mamdani, who just won the Democratic mayoral primary. Here’s a New York Times writeup with some background. Here’s a less-flattering take on his economic policies by my employer’s editorial page that didn’t make it into “all the news that’s fit to print.”

Draw your own conclusions. I’m interested in why some friends and acquaintances who do live in New York see things so differently than me. Less-educated and single-issue voters are easily-swayed, but what’s the appeal for people who have read and traveled widely?

I think it’s because they don’t understand that safety and prosperity aren’t guaranteed and that they might not have to suffer if they’re wrong about radical policies. I hate resorting to composite sketches, but I’ll make an exception and engage in some insensitive stereotyping because, like I said, our backgrounds explain so much.

This person lives in New York but wasn’t born there, only having moved here as a young adult after Times Square was Disney-fied. One and probably both parents are American-born and they grew up in a small town or in suburbia.

They went to a good and possibly elite university and might have a master’s degree in something like journalism, education or public policy. With the amount of money mom and dad or grandpa’s trust fund paid in tuition, or what they took out in unwise loans, they could be making way, way more with a similar professional degree in law, finance or medicine.

They’re cool with that because those people are, in their assessment, soulless drones or sell-outs. There’s a certain nobility in semi-poverty. Sure these people pay enough in rent that they could have a material standard of living far above their cramped co-op or rental in Prospect Heights if they lived in Dallas, but then they’d have to live in Dallas.

Little Atticus and Clementine like the neighborhood so much and the French immersion at PS 321 is wonderful. Grandma is paying for a tutor and it looks like both have a shot of getting into Hunter. She also might be able to help out if they wind up going private—Grace Church or Berkeley-Carroll would be nice.

Sorry. To be clear, I think people fitting the above composite make cities hip and vibrant. They keep weird ethnic restaurants, cool bookstores, and art cinemas in business. They don’t jump the turnstile, they give back more than they take and they add to a city’s cultural appeal. Long may the graduates of Oberlin, Northwestern, and Middlebury migrate here and make it their home—the next craft IPA’s on me!

So, on to my perspective. I was born in Queens in 1969 to Hungarian émigrés and didn’t really speak English until I started school. I wasn’t aware of such things at the time, obviously, but between then and the time I started first grade close to one million people had left the city because of crime and deteriorating public services. Here’s the famous “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD” headline when it was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in 1975.

I’m not trying to paint you some picture of an Oliver Twist upbringing amid urban horrors—it was fine. My sister and I were latchkey kids raised by an educated, loving single mother. But the normal 1970s New York City stuff happened to us: Petty crime, overcrowded classrooms, and nervously riding dirty, graffiti-smeared subways. My sister’s best friend and her little brother, who lived around the corner, were shot and killed when she was in third grade.

I had 43 kids in my fifth grade class and distinctly remember sharing desks and using a textbook so old that it referred to America having 48 states. The summer of 1977, between second and third grade, was memorable. There was a 25-hour blackout that resulted in widespread looting and the Son of Sam murdered someone in our neighborhood. When my grandmother told me that he’d been caught I felt so relieved because I was worried about my mom coming home from work by herself at night.

Speaking of her work, it was at the infamous Manhattan State on Ward’s Island between Manhattan and Queens—an institution where the city used to put people once called “criminally insane.” In the 1970s, after effective antipsychotic drugs were invented and budgets were slashed, these places were thinned out. You can see plenty of people on the subway or street today who might have been residents back in the day. A lot clearly aren’t taking their meds.

That left my mom with a smaller but really lovely set of patients. It was a scary place and a colleague of hers lost an eye after being stabbed with a fork. One of the final straws came when she was attacked (we left the city just before I started junior high). The aides who were supposed to stop that weren’t doing their job and she was only saved by another patient. There was very little accountability for state and city employees and the nurses would walk out every day with food and paper goods under their coats stolen from taxpayers.

Why is coming from behind the Iron Curtain significant? Because deciding New York has become too crazy is an option if you’re American and your mom and dad live somewhere safe and boring and speak English. It isn’t when you’re the only person in your family in the entire country earning a salary, able to drive a car or who can function as an American adult. There’s no moving back home, and growing up in a communist country has already given you a brutal lesson in the utter folly of policies that are contributing to the decay you see in your new home.

If you’re lucky you get approached about moving somewhere very alien where they’re desperate to take advantage of hard-working people like you but can’t understand your accent, which is what she did—another story for another time. Lots of poor New Yorkers today don’t have that option if the city starts to look and smell like the 1970s.

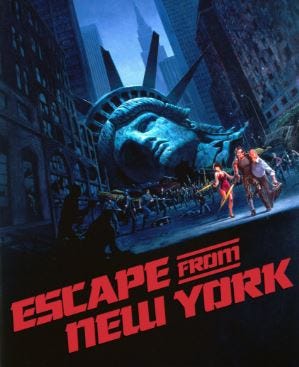

How did people feel about the future of New York City back then? The year we “escaped” from New York the movie “Escape From New York” came out. It takes place in a dystopian 1997 and Manhattan has been turned into a walled-off prison. It’s ridiculous, but I remember watching it on cable TV shortly after we got out of town and thinking: “Yeah, could happen.”

It was around then that my uncle, who literally escaped from Hungary in 1966, discovered he could make more money as a master plumber than as an engineer. He worked very hard and did a job on some buildings in Greenpoint in Queens. When the owner couldn’t pay him he took possession of them through something called a “workman’s lien.”

The joke was on him—for a while—because nobody wanted the buildings in that blighted area and he had to pay the taxes. Today the neighborhood is full of hip apartments, coffee shops and clubs. People who moved here after 1985 or so and moan about the cost of finding a place to live can’t imagine a time when people were overjoyed if you showed up to buy their apartment. My mom looked at a six-room place on East 95th Street in Manhattan in 1977—we were renters then—and could have paid $26,000. Those apartments go for millions today.

The catch was that there wasn’t school choice like they have now. My sister and I would have gone to a much rougher one in Spanish Harlem than out in Queens.

If you’re middle class, but even if you’re working class, New York City is incomparably more livable today than it was then. That didn’t just happen magically. It took a few good mayors and a long boom on Wall Street. The crack epidemic and the not-so-good Mayor Dinkins set that back a bit during the only years I lived in Manhattan (I was a grad student at Columbia). Homicides peaked at six-a-day in 1990, but it’s been a mostly improving trend.

People from other parts of the country sometimes don’t believe it, but New York is safer than several U.S. cities today. Even Bill de Blasio—or “that communist,” as my mom calls him—wasn’t incompetent enough to really hurt things that much.

But my friends and acquaintances shouldn’t push their luck. Demonstrably dumb ideas like rent control, taking over supermarkets to keep grocery prices down and cutting back policing will leave a mark if they coincide with a downturn in the economy.

And why they feel okay with having a culture warrior as mayor is beyond me. That isn’t his job. Back when Abraham Beame was mayor and Ford told the city to drop dead, we didn’t have today’s divisive politics.

I believe some people would take malicious pleasure in seeing New York City suffer if the transit system, the regional tunnels and bridges or the entire city found itself short of cash and this guy went to Washington, cap in hand. New York isn’t going to enter an “urban doom loop” that places like St. Louis, Missouri have because it’s too vibrant. Even so, dumb policies and incendiary speech at a time when Wall Street money stops paving the streets with gold is flirting with disaster.