A year ago, the concentrated financial power and frustration of millions of novice stock traders rocked Wall Street, alarmed Washington and turned journalists into armchair sociologists. The stranger-than-fiction story sent both publishers and Hollywood studios scrambling to tell it. I’m one of the lucky people who got paid to delve into GameStop mania in the form of a book and I was surprised by much of what I learned.

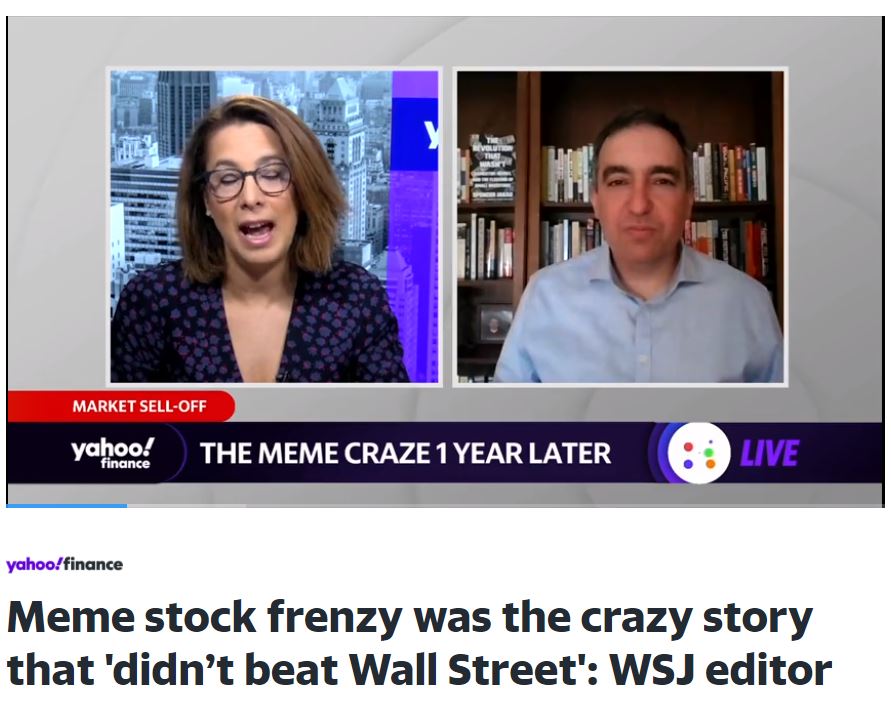

“The Revolution That Wasn’t” might sound like a “nothing to see here folks” type take, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Sure the efforts of millions of mostly young speculators to stick it to the man and make a fortune in the process didn’t live up to the breathless headlines of late January 2021. They actually delivered Wall Street and already rich corporate insiders a massive payday. Yet they also showed the awesome power that apps we carry on our smartphones can have over markets.

I get asked frequently whether another stock will rise from obscurity to become a national obsession again. Probably not quite the way that GameStop did: The crowd’s energy has surged again and again into fruitless attempts to recreate last January’s magic that require “diamond hands” – holding onto crumbling meme stocks no matter what to effect the “mother of all short squeezes,” but professional investors are no longer asleep at the wheel. The more interesting question is why GameStop mania happened in the first place. I often think of this quote to put things into context:

“We find that whole communities suddenly fix their minds upon one object, and go mad in its pursuit; that millions of people become simultaneously impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first.”

Charles Mackay wrote that passage decades before anybody could describe themselves as a psychologist. He was a journalist, like me, and his classic, “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds,” was published in the midst of Britain’s 1840s Railway Mania. His description of that and other episodes like the South Sea and Mississippi bubbles and Tulip-mania in the preceding centuries are rich with insight into human nature. We have been through numerous manias since then as well – most recently dot-coms and housing. History doesn’t repeat, but it certainly rhymes.

As a long-time investing columnist for The Wall Street Journal and a student of financial history, I still was surprised at some of the new twists to this age-old pattern in the GameStop story. The human psyche hasn’t changed, but Wall Street and Silicon Valley’s understanding of it certainly has. Nobody working at stock brokerages like Robinhood or social media firms like Twitter, TikTok, or Reddit predicted that an informal army of amateurs would blow multi-billion dollar holes in major investment firms for fun and profit. They surely understood, though, that they were pushing psychological buttons that could enrich them at the public’s expense.

Take reinforcement. Since behaviorist B.F. Skinner’s experiments on the variable reward ratio in the 1950s, games of chance such as slot machines and their digital equivalents have been designed to provide stimuli that, for far too many people, lead to addiction. While the stock market isn’t really “a casino,” as some critics contend, the newest generation of smartphone based trading apps borrow heavily from the gambling world to create engagement. Robinhood, which has captured about half of all new brokerage accounts opened in the past five years, has been sued for using animated confetti and giving away free shares of widely ranging value–a lottery-like prize– for opening accounts and referring new customers.

Today it is nearly free and effortless to be an investor by buying and holding diversified index funds and it is becoming common knowledge that even the pros can’t beat those plain vanilla products 80 percent of the time. But index funds are far less profitable for the industry. Instead of having them “set it and forget it,” checking their portfolios occasionally, online brokers have convinced some customers to trade thousands of times a year. Robinhood’s active users check their accounts several times a day.

“You were born an investor,” claim its ads targeted at young people. Their costly level of hyperactivity is in part due to the “illusion of control” described by Ellen Langer’s experiments in which people put an irrational value on personal agency. That is why lottery sales are far higher when people can pick their own numbers despite identical odds.

Meanwhile, the Dunning-Kruger Effect–the behavioral bias that makes novices overconfident in their abilities–was put on steroids by the pandemic. The wave of new account openings coincided with both the arrival of pandemic stimulus checks and the quickest rebound ever from a bear market in 2020. In a trend never seen before, 96 percent of stocks would rise in the ensuing year, making investing look easy. Dave “Day Trader” Portnoy, himself a newbie who boasted that he was better than 91 year-old legend Warren Buffett, would livestream himself picking tiles out of a Scrabble bag to choose stocks to his huge social media audience. Success, as they say, is the worst teacher.

And when they opened the app, Robinhood and its many imitators showed them the day’s most active stocks for a reason–to stoke the fear of missing out. Studies have tied acting on FOMO to feelings of regret. When the newest speculators buy too late or sell too early to make a score, they are encouraged to keep trying, as exploited by gambling establishments through the near miss effect (like when a slot machine displays two of three cherries or the ball in roulette falls one slot away from giving you that big payoff).

Of course so many people with so little money turning themselves into a major force in the market wouldn’t have been possible a generation ago. Trading stocks has become progressively cheaper. Robinhood was the first successful broker to charge nothing for a trade, though.

Trading isn’t really free–huge market makers gladly pay brokers to fill their customers’ orders–but the fact that small investors who have never paid a commission in their lives perceive it as costing nothing has triggered the “zero-price effect” described by behavioral finance experts. Demand normally rises when prices fall. The formula goes haywire, though, once prices hit nothing for something that also entertains us. Trading stocks for “free” has been made so much like a game that retail activity has exploded.

This shift to zero at every major broker happened just in time for the pandemic, which supercharged locked-down and bored young people’s speculative tendencies. And because they got “house money” via stimulus checks, investors’ sometimes crippling fear of financial loss as described by Prospect Theory was short-circuited at a critical time. Millions opened accounts, many of whom had already dabbled in recently-legalized sports betting, and they found they liked stocks even more. The sharp market rebound from the initial pandemic plunge created unprecedented volatility and excitement. And brokerages’ irresponsibility in allowing newbies to trade complex stock options, with their asymmetric payoffs and finite time horizon, made investing resemble sports betting.

But what to buy? Young Americans’ love of social media meant that it was “finfluencers” like Portnoy rather than Mom and Dad’s broker at Morgan Stanley who provided ideas. The most influential voices were the most confident and often the wildest. And it was those stocks that did best for a while, reinforcing the wisdom of following the crowd. The top 100 stocks highlighted by Robinhood on its app rose by 102 percent in 2020 according to an index created by newsletter writer Noah Weidner–some six times as much as the benchmark S&P 500. Baskets of companies with no profits or those heavily shorted by skeptics also had a great year.

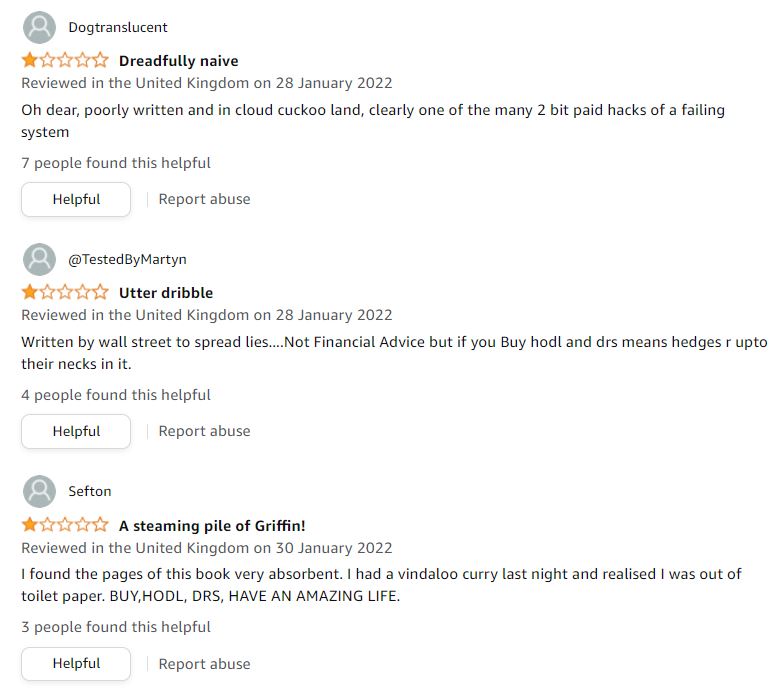

And, because Millennials and Gen Z share private information online so readily, those bragging about big scores on those stocks often backed it up with screenshots of their brokerage accounts. This triggered a phenomenon called social proof in which apparently successful people, even if they were just lucky, gained undue influence.

Virality was instrumental in the runaway popularity of small, money-losing companies. On Reddit’s r/wallstreetbets in particular, which would become the epicenter of the GameStop squeeze, reckless wagers in crowd favorites were the most likely to become “upvoted” and hence visible to somebody logging on. The wave of buying would become self-reinforcing and the support of certain stocks has become tribal and almost cult-like for some who dub themselves “apes” and who subscribe to conspiracy theories involving nefarious hedge funds and even journalists like me.

As of this writing, the thrill of overnight fortunes made and lost last year hasn’t faded for many trading novices. With the exception of those who are turning meme stocks into an obsession, though, the spell will break eventually. As Mackay sagely wrote 180 years ago:

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, one by one.”

(This post originally appeared on LinkedIn)