Your anxiety is someone’s profit margin

I was reminded recently of how expensive a bit of nervousness can be when combined with clever marketing (screenshot below). My youngest son is off to college in a month, which makes his mom and me proud, excited, and just a little weepy. It also leaves us poorer–the cost of college is no joke! I may actually have to charge for my blatherings in this newsletter some day.

We went into it with eyes wide open and will be fine, but any large expenditure tends to make people anxious. I distinctly remember one of my closest friends calling me the night before signing the papers to buy his house in London to ask if it was normal that it worried him more than getting married or having kids.

Yes, he’s normal (well, in that respect). I was about a year ahead of him on all three major life events and felt exactly the same way about it–like I was some sort of sociopath. We humans spent 99% of our existence as hunter gatherers or in subsistence agriculture. Instead of catching a gazelle, we bring home a paycheck and try to save some of it. Money is the stored-up fruit of our labor. It confers social status and also ensures survival since we’ll depend on it to sustain us and our families one day.

By parting with a chunk of it all at once, or borrowing and pre-spending our future wages, we’re getting something we value at least that much but also bothered by what feels like a mortal risk. Whether it’s a physical object like a $900 iPhone or an experience like the $90,000 annual sticker price for some elite colleges these days, bad things occasionally happen. You might crack your screen as soon as you enter your contacts into your phone or your kid could drop out a few months into what should be four fun-filled years, missing out on a prestigious degree.

But we overestimate the actual benefits of hedging against bad stuff happening after a big financial commitment–and not by a little. That supports businesses worth billions of dollars a year. Literally a day after our payment cleared for my son’s yet-to-begin first semester, we got this:

His college, and it seems pretty much every other private and public institution in the U.S that I looked up, has “partnered with” – that’s the language they all use – companies like A.W.G. Dewar and GradGuard that are backed by larger insurers, including AXA. This is the 3rd prompt I’ve received to consider signing up for a specific insurer’s product, with their emphasis in bold, so I assume it confers some financial benefit to the university.

In the case of my son’s college, a refund for 75% of tuition, room, and board costs $676 per semester. It is “meant to safeguard your financial commitment.”

Hmm.

It depends to some extent on how much you’re paying because most students receive aid and don’t pay full freight. Using GradGuard, which makes it easy to get a quote for different out-of-pocket amounts (sorry guys, “Ab Cd” will not be purchasing coverage), I said that my child’s cost of attendance would be $40,000 a year at Harvard University, one of their “partners.” The quote for a year of coverage living on campus for an out-of-state student was $1,554.

At first blush that doesn’t sound so excessive compared with the full outlay–less than 4%–but what’s covered? Not sitting in your dorm room smoking pot and flunking your classes. (Dropping out to start Microsoft or Facebook don’t count either, but I suppose the Gates and Zuckerberg families aren’t pestering their sons any more about how much money they wasted on Harvard tuition).

Your student has to have an “illness, injury, or medical condition…disabling enough to make a reasonable person completely withdraw from school.” In the case of mental illness, a licensed professional must advise them to “withdraw completely.” Pre-existing conditions? Nope, not unless specifically waived. Nothing “foreseeable, intended, or expected.” Was the kid injured while training for an amateur sport? Sorry. Committed a crime? Tough luck. School ceased activity (it’s happening more and more)? Not that either.

And what if one of those approved things happens once you’ve paid but not yet begun class. The standard formula seems to be a 100% refund from the college itself, so the insurance will have been in vain. In the case of Boston College, which seems pretty typical, you then get 80% of what you paid back the first week, 60% the second week, 40% the third week and 20% the fourth week. It sounds like it can be for any reason and, if memory serves from the late 1980s, the early weeks were when most kids who decided this college thing wasn’t really for them quietly left.

So let’s say Mom and Dad have paid half of that annual $40,000 for a semester and Junior comes home after 10 days. They are out-of-pocket $8,000 (plus $1,554 if they bought insurance). Looked at another way, though, they just saved $152,000 in tuition over the remainder of those four years, plus $4,662 in tuition insurance they now won’t be coaxed into buying. So what is sold as protecting your “financial commitment” actually is a bit of an unexpected windfall.

But that’s not all. If Junior enters the labor force directly instead of college–a completely respectable choice–he’ll easily make $100,000 over the next three-and-a-half years that he wouldn’t have as a student. Or if he enrolls in community or state college instead the family will at least save tens of thousands compared with the private institution’s sticker price. His education probably will be quite good and less-likely to be disrupted by an, er, “autonomous subgroup”.

So what financial calamity were you insuring against? And what are the odds that a previously healthy 18 year-old will be ill or injured enough, but still sufficiently with-it, to get a doctor to document it within the prescribed time limit and receive a payout?

Oh, there’s also death. Thankfully that’s rare too, but what sort of consolation is that for the grieving family? “Hey, Junior died in a car crash, but at least we got his last semester’s insurance back!” (Side note for those who’ve seen child life insurance advertised on TV from Gerber, the baby food people–this is a grotesque product and a ripoff. Here’s the White Coat Investor with his thoughts).

I can see why people buy this insurance, but not why they should. And I wonder how much the vendor–in this case the school–gets out of the bargain.

That certainly is the model for those “protection plans” you’re invited to pay for when buying an expensive piece of electronics. The store makes a better margin on insurance, often provided by a third party, than on what you just bought. For example, Best Buy’s Geek Squad protection for an $800 smartphone costs $9.99 a month for up to two years. A new phone has a manufacturer’s warranty so this would cover an accident and then kick in for mechanical defects after that period expires. But there’s also a $199 “service fee,” otherwise known as a deductible, on top of the $240 you’d pay for two years. So it costs you up to $440 to “protect” that $800 phone which the Geek Squad will fix or replace with a similar model. And how much is that now two-year old phone worth if purchased refurbished? Not $800.

A similar thing I see every time I buy plane tickets or book a VRBO these days: “Protect your trip!” You typically are about to check out and could lose your booking so there isn’t a lot of time to think about the financial pros and cons–perfect conditions for an ill-considered purchase.

Buying something like medical cover while abroad might make sense, but not reimbursement for canceling your trip for one of the narrowly-defined reasons in the fine print. Say I booked a trip to Europe and had to cancel because someone not traveling got ill? It has to happen during the trip. Death in the family? Ditto.

From insurer Generali, which writes a lot of these policies: “Your or your traveling companion’s sickness or injury must first occur during your trip in order to have coverage. Pre-existing medical conditions are generally excluded from coverage.”

And protecting what you paid for a rental before traveling? It’s certainly possible you’d invoke the policy, but then, as with tuition insurance, you’d also avoid a bunch of expenses you might have incurred during your trip. A ruined vacation stinks, but, financially at least, you’re better off. And even if you get your money back, it won’t give you another week of paid time off. For working people–especially Americans–time is scarcer than money for a vacation.

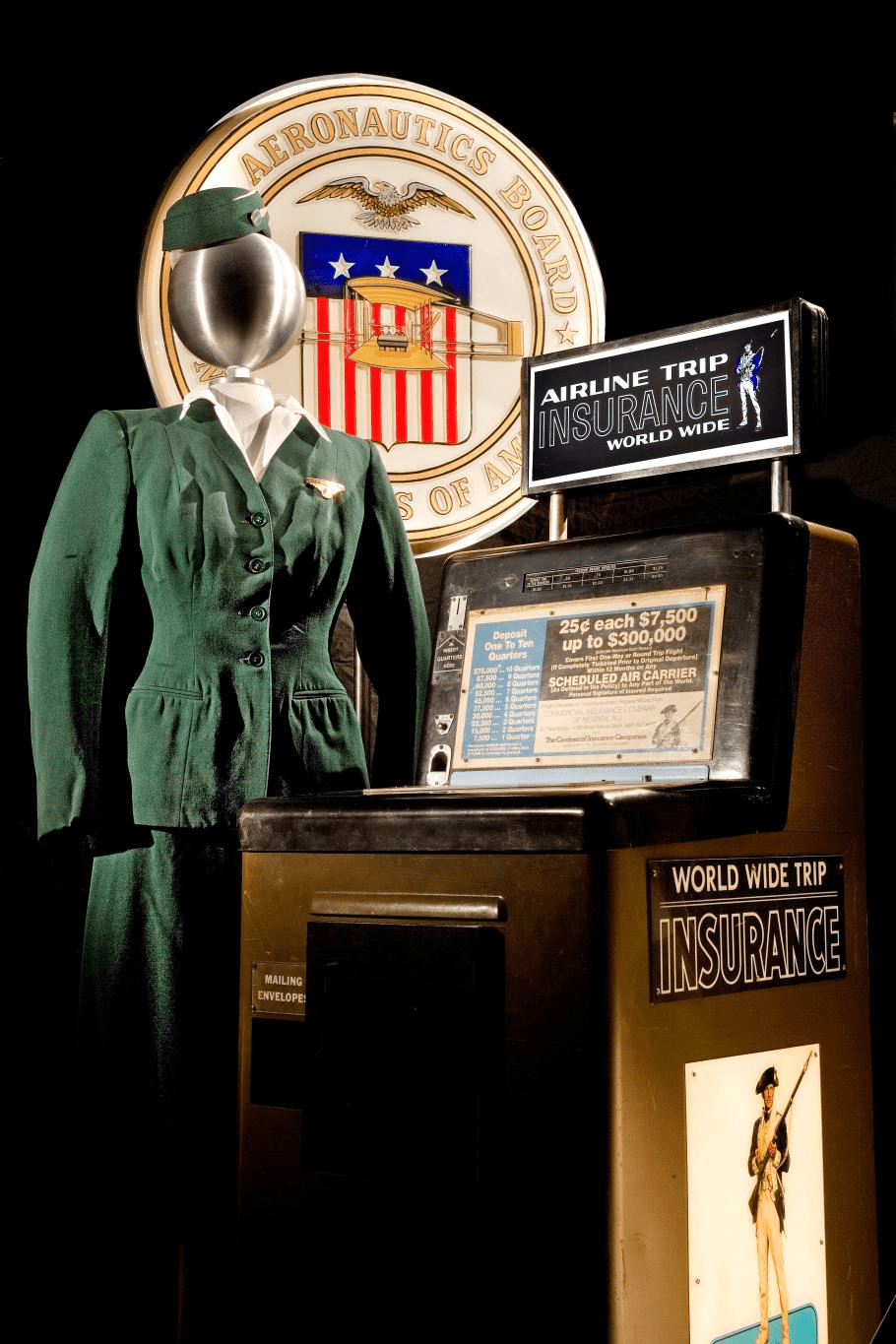

The dumbest insurance scheme of all no longer exists. When I was a kid there still were kiosks at airports where you could put in a small amount of cash, fill out a form, and, if the plane you boarded crashed, the beneficiary would get a payout. There’s an old machine on display at The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum (pictured). It cost a quarter for $7,500 of coverage.

A publication called Insurance Business Magazine recounts a lawsuit from 1963–the dawn of the jet age and a more dangerous time to fly than today–that laid bare the numbers. It said that “a recent annual report filed by a group of underwriters who handle a large portion of air trip insurance business in the United States, showed total premium collections for the year to be $3,382,561. In the same year the group wrote air trip insurance for $84,564,025,000 and paid out $1,388,839 in losses.”

That is just wildly profitable (even with the occasional plane blown up by relatives who had taken out policies). Fortunately the business has disappeared as people aren’t as afraid of flying–nor should they be. According to the most recent data from an industry body through 2021, there had been just two domestic fatalities in total since 2010. Even in 2009 when there were 50 it came to 0.010 per 100,000 departures.

Is insurance generally a scam? Not at all. I personally am insured to the gills–both the mandatory types like home, auto, and health as well as term life and even umbrella insurance. (Unless you understand what you’re buying or are doing it as some sort of estate planning, high net-worth tax boondoggle, don’t buy more than a cheap term life policy to cover your productive years).

Term insurance makes sense. There’s a low probability of my dying while the policy is in force and the market is transparent and competitive enough that I know the insurance company is making only a reasonable profit for their risk. If all goes well my family will never see a penny back. The insurance company verified that I don’t smoke or use drugs, checked my weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, and family history and made me an offer. I’m reassured that I’m not subsidizing an overweight skydiving chain smoker who got the same price.

That is what insurance is–pooling risks to protect you against an unexpected financial blow. Don’t buy it as a way to assuage buyers’ remorse.

(This post was published earlier on my new Substack newsletter, which is free).