I’m in the process of clearing out my basement and, as dusty old boxes sometimes do, the contents of one took me on a trip down Memory Lane. They also made me think about a lesson I learned that investors would do well to understand today.

The artifacts were the lucite “deal toys” from various initial public offerings and secondaries I worked on as an equity analyst. These usually adorn the desk and then, as they get more senior, the office of any self-respecting investment banker. Lots of trophies made you a “big swinging dick.” Fighting my hoarder tendencies and my ego, I dumped them in the trash.

But there were three rectangular hunks of clear plastic in that box that I kept: my Institutional Investor awards. Back then at least, the best thing you could do for your career as an analyst was to be “II ranked” in that magazine’s annual survey of fund managers–coming in among the top three in a category. And if you were number one then the magazine would write a flattering blurb with anonymous quotes and a caricature artist would make a drawing of you as an athlete–football in the U.S. and soccer in Europe. Your face also was on the cover of the magazine. It figured heavily into your career prospects and bonus. Andy Kessler wrote a nice piece about it back in 2001 when I was still in the business.

As soon as I heard about this, I made it my goal to be on that magazine cover, and for three years in a row I was. Is that because I was so good at picking emerging market stocks? I suppose I was okay, but it really was a measure of how much clients liked and valued you. For most of them that meant how often you called, how ready you were to organize trips and entertainment for them, and how smart you made them feel. I remember hearing one of our large clients repeat almost verbatim to a bunch of his clients, a group of pension consultants–a rare peek for me at how that particular sausage was made–part of the presentation I had recently given him. He got a detail or two mixed up, but I don’t think they noticed.

But before my Institutional Investor glory and all those 90 hour weeks and client ass-kissing, pretty much exactly 30 years ago, I was wet behind the ears and, to quote Liar’s Poker, still “lower than whale shit on the bottom of the ocean floor” at dear-departed CS First Boston. Our then-largest client asked me about two Eastern European companies and I told him that I was pretty sure one was run by a crook and that the other one, despite being backed by some well-respected financiers, was headed for bankruptcy. Much to my surprise, the client wasn’t happy that I had shared this opinion with him and bought more of them instead of the stock that I recommended.

A salesman covering the account who had way more Wall Street experience than almost anyone on my team took me out to lunch in Budapest that summer of 1994 and clearly was exasperated at what a dummy I was. “Spencer, if the man wants a purple suit, sell him a purple suit.” In other words, we’re in the selling business. If someone wants to do something dumb then he’s a big boy so just make sure we’re the ones who get the fat commission.

I remember feeling like a little kid learning that there‘s no Santa Claus*, but he was absolutely right. One company went bankrupt and the CEO looted the other one. A competing analyst got quite a bit of attention for a brilliant exposé about him and his offshore dealings and I remember feeling envious–probably an indication of why I later went into financial journalism. But I made way more money than her in the business and got to be on those magazine covers, so there’s that.

Even after all these years, Wall Street isn’t so much in the advice as in the customer satisfaction business. Last week I saw one of my former Wall Street Journal colleagues, Eric Wallerstein, on CNBC. He was a brilliant financial scribe and I’m sure he’ll do really well in his new role as chief strategist at Yardeni Research. But in an interview on “Closing Bell,” Scott Wapner immediately gave him a hard time because the firm he had just joined hadn’t raised its S&P 500 target for the end of the year. The figure had already been reached after a torrid first half. Everyone else was doing it, and Eric said he still liked the market, so why not raise it?

The interaction tells you how un-serious financial media can be. First of all, if I remember correctly, Eric’s boss, Wall Street veteran Ed Yardeni, had set a 5,400 point target in 2023 when the S&P 500 was around 4,000, so he made a good call. But I’m pretty sure he doesn’t possess a crystal ball to tell you where an index, much less an individual stock, will be trading in six months.

There’s nothing like a rapidly rising market to make people even more confident in stocks, though, so CNBC’s viewers were looking for a number to underpin their optimism. I hate to sound so dismissive of my former profession: Analysts and strategists work hard and do a lot of useful things, but spending thousands of hours writing hundreds of pages to tell people what they want to hear with a false degree of precision isn’t one of them.

A prime example of the horse following the cart comes from the market’s now-favorite stock, Nvidia. If an analyst had been really, really smart then he or she might have guessed that AI chips would be worth their weight in gold and that Nvidia would get a lot more valuable.

But last April, with the stock at $27.75, analysts’ price targets all clustered at or slightly above that level with the average target being 2.3% higher. There were no three-digit price targets (the stock has since split so I mean on the current number of shares). Any analyst who had stuck his or her neck out and said that would be a legend but probably would have been doing it to gain notoriety like Henry Blodget and his infamous “Amazon $400” call in 1998. Merrill Lynch soon fired its analyst covering Amazon and hired Blodget from second-tier broker CIBC Oppenheimer for a princely sum.** It isn’t worth the career risk of making a prediction like that for someone already working at a top firm. And if you are going to stick your neck out at a big bank, try to be an optimist. This week JPMorgan Chase dumped its strategist, Marko Kolanovic, described as “the biggest bear” on Wall Street for, among other things, missing the AI boom.

Back to Nvidia: Fast forward to last July and the price and the average target had jumped dramatically to $46.75 and $50.09. By this January those numbers were $61.53 and $67.45. In April it was $86.40 and $99.70, respectively, with analysts racing to keep up. At the end of June 2024 it was $125.83 and $129.01 with not a single “sell” recommendation out of 62 analysts polled by FactSet (55 “buy” or “overweight” and 7 “hold”).

Yes, good things have happened. No, it isn’t the case that any serious discounted cash flow model making good faith projections instead of looking at the stock price spit out exactly $28 last April and $128 today. That doesn’t mean the latter number can’t be right, or even too conservative, but it does tell you that analysts are watching the price rise and telling their customers what they want to hear.

As another recently-departed WSJ colleague, Charley Grant, wrote as his swan song this past week, “No Nvidia in Your Portfolio? You’re Just Toast.” For both analysts and fund managers–the ones who pay them and vote in those surveys–not being on board has been career suicide. At the time of Charley’s article, Nvidia stock was up a whopping 149% year-to-date compared with 4.1% for the average S&P 500 stock so just missing that one name, or even worse some of the others lifted by AI mania, would devastate a fund manager’s relative returns. And forget about getting your caricature on that magazine cover if you insist Nvidia is really worth $50 a share and stick to your guns.

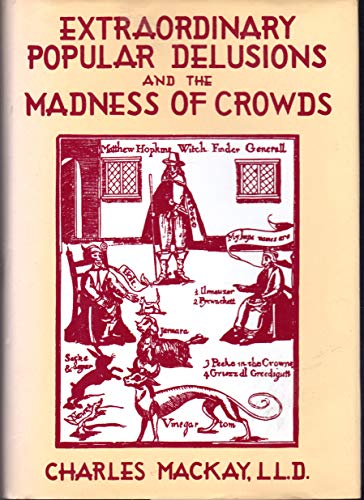

If you’re reading this and you aren’t paid a salary by Wall Street then take note: Your career isn’t at risk if you don’t own the latest hot thing. You might have one less thing to brag about to your friends, but don’t let groupthink or FOMO make you do something that leaves your spidey-senses tingling–you’ll be better off in the long run. The next time a well-paid investing professional makes a persuasive case for something that doesn’t feel or sound right to you, just picture this guy in your mind.

*I felt almost the same way a month into my current career as a journalist when I was told that it really didn’t matter if I wrote well since that isn’t what I get paid for.

**He was later banned from the securities industry for life.